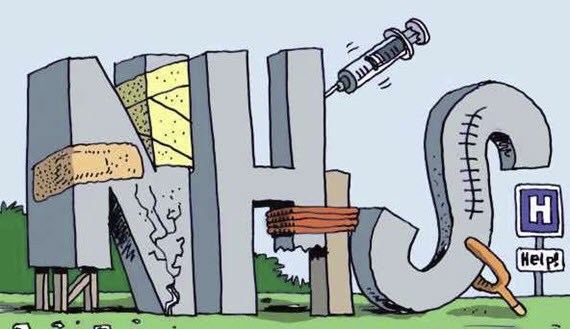

Happy Birthday, sacred cow – where next for the NHS?

David Crozier

The National Health Service is 70 years old this month. On 5th July 1948, Health Secretary Aneurin Bevan launched a new system, whereby healthcare from whatever source – medical, dental, optical; hospital or GP – was to be brought under one umbrella.

At the same time, for the first time anywhere on the planet, healthcare became free at the point of delivery. For everyone.

There is absolutely no doubt that this innovation has saved many lives and improved the lot of millions. Prior to that, every visit to the doctor, every hospital appointment cost money; and while there is no doubt that many GPs treated people who could not afford to pay, many did not, and there is ample documentary evidence that people died in their thousands simply because they could not afford medical attention.

For all its faults, and for all our grumblings about it, the NHS is one of the best examples of a national healthcare system anywhere in the world. Under its aegis, the UK pioneered many developments in medicine and surgery, including the world’s first nationwide breast-screening programme and the world’s first successful human in vitro fertilisation, to name but two revolutions that mean there are thousands upon thousands of people alive today that would otherwise not be with us.

It does so with remarkable efficiency. Although near the bottom of spenders in terms of health, the NHS is one of the best and safest healthcare systems out of 11 developed countries studied. The UK spends a little more per capita on the NHS than the US does on Medicare and Medicaid† alone, on top of which the US system spends multiple times this level through privately funded healthcare, and its health outcomes are no better than those from the NHS.

But the main fundamental innovation, right from the outset, was that healthcare was to be free at the point of delivery, and it is this aspect that the UK public are most fiercely protective of: a staggering 91%‡ of the British public continue to believe that the NHS should be definitely or probably be free at the point of delivery.

As we have seen, time and again, any attempt by Government to meddle with or water down this principle has led to protests and strikes, and a level of political backlash that is evoked by few other issues.

The problem is that we are living longer and longer, which has two consequences: the longer we live, the more goes wrong with our aging bodies and minds; and the cost of some of the treatments that are contributing to us living longer are phenomenally expensive. Compare the cost of CAR-T± at £340,000 per patient to extend end of life by a few months, with £5,600 for a hip replacement, or £8,500 for a heart bypass, both of which will, all other things being equal, add many years of comfortable living to people. Which is better value for money for the country as a whole?

Of course, try having that discussion with the person, or the parents of the child, needing the experimental treatment! A very reasonable argument can be made that there is no straightforward equivalence between human life and health, and what it costs to preserve it.

Yet there is, without doubt or argument, a significant cost to providing a National Health Service, and it has always struggled with money. We read of waiting lists today and some of the stories are horrendous, without doubt, yet it was always thus. From its very inception, the NHS has been swamped by demand, leading in 1951, only three years after its birth, to the introduction of charges for prescriptions, and dental and optical care. Nye Bevan, dyed-in-the-wool Socialist that he was, saw this as a betrayal of the founding principles of the NHS and the welfare state, and immediately resigned.

Some argue that the answer is more funding; but the NHS is pretty much a bottomless pit. For all the reasons discussed – lengthening lifespans; more treatments, costing a lot of money – the NHS could swallow all the money that could conceivably be thrown at it and still ask for more. The difficulty is that there are other priorities – education, infrastructure, defence, to name but three – that the country also must pay for, so regardless of where you think the NHS is this pecking order (and the public is pretty much agreed that it’s right at the top, and nailed on there) any more money given to it has to be at the expense of something else.

Unless, that is, you are willing to pay a bit more tax. If so, you are not alone. A recent survey‽ found that between 62% and 66% of people would be willing to pay more tax to help fund the NHS. In addition, more and more people with the means to do so are turning to private medical care, rather than wait months or years for alleviation of chronic conditions.

Either way, it is looking increasingly likely that we will have to pay more for the cost of medical care in the years to come, either through increased taxes, or by paying for private care.

The natural human lifespan is* “threescore years and ten”, or maybe “fourscore years” – it remains to be seen whether the NHS will survive much longer than this without major surgery.

As ever, I would be glad to hear any comments or questions this email might provoke. Please feel free to get in touch with myself or one of the team if you have any financial planning matters requiring attention.

David Crozier CFP

Chartered Financial Planner

‡The King’s Fund, August 2017

†Government provision in the US for older people and those who cannot afford health insurance

±An experimental cancer treatment

‽The King’s Fund/Ipsos Mori August 2017

*Psalm 90:10